21th December 2013 Partial reversal of aging achieved in mice Researchers have achieved a major breakthrough in the study of aging. By using a chemical that occurs naturally in the human body, it was possible to restore tissues in two-year-old mice to a much younger state.

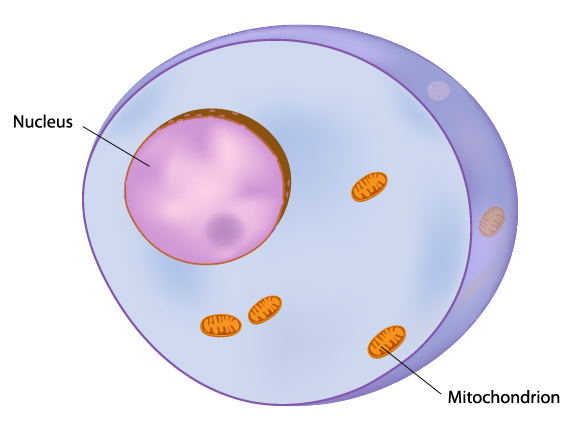

Harvard Medical School, the National Institute on Aging, and the University of New South Wales, Sydney, collaborated on a joint project, the results of which are published in Cell. Harvard Professor of Genetics and senior author of the study, David Sinclair, had previously shown that resveratrol – a compound in red wine, grapes and certain nuts – activates a gene known as SIRT1 that improves health and longevity in animal subjects. Ana Gomes, a researcher in the Sinclair lab, had been studying mice in which this SIRT1 gene was removed. As expected, mice without SIRT1 showed greater signs of aging, including damage to mitochondria (energy-producing "powerhouses" within cells). What surprised the researchers, however, was that mitochondrial proteins coming from the cell’s nucleus were mostly at normal levels. Only proteins encoded by the mitochondrial genome were reduced. “This was at odds with what the literature suggested,” according to Gomes.

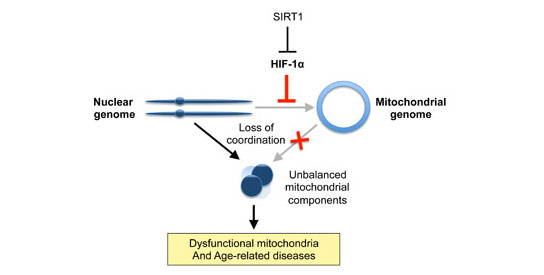

In their subsequent research, they discovered a chain of extremely important events that occur in the cell. A chemical known as NAD (which declines as we age) enables SIRT1 to control the behaviour of a disruptive molecule called HIF-1. Without sufficient NAD, the SIRT1 is unable to prevent the HIF-1 from interfering with cross-genome activity, and this reduces the cell's ability to make energy, leading to aging and cell damage. The SIRT1 therefore has an intermediate role, almost like a security guard. As long as communication remains smooth between the nuclear and mitochondrial genome, cells stay healthy. While the breakdown of this process causes a rapid decline in mitochondrial function, other signs of aging take longer. Gomes found that by administering an endogenous compound that cells transform into NAD, she could repair the network and rapidly restore communication and mitochondrial function. If the compound was given early enough – prior to excessive mutation accumulation – within days, some aspects of the aging process could be reversed. "The aging process we discovered is like a married couple. When they are young, they communicate well, but over time, living in close quarters for many years, communication breaks down," commented Sinclair. "And just like with a couple, restoring communication solved the problem."

Examining muscle from two-year-old mice given the NAD-producing compound for just one week, the researchers looked for indicators of insulin resistance, inflammation and muscle wasting. In all three of these cases, tissue from the mice resembled that of six-month-old mice. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old in these specific areas. Dr Nigel Turner, from the University of New South Wales and co-author of the study: "It was a real surprise to see the markers of aging move back so quickly in just a week. Now that we understand the pathway, we can look at other ways to restore the communication and reverse the aging process. People think anti-aging research is about us wanting to make people live until they are 200, but the goal is really to help people be healthy longer into old age. We know that this cell communication breaks down in diseases such as dementia, cancer and diabetes. This research focused on muscles, but it could benefit multiple organs. Whether that means we’ll all live to 150, I don’t know, but the important part is that we don’t spend the last 20 to 30 years of our lives in bad health." Professor Tim Spector, of Kings College London, commented: "This is an intriguing and exciting finding that some aspects of the aging process are reversible. It is, however, a long and tough way to go from these nice mouse experiments to showing real anti-aging effects in humans without side effects." While human therapies are likely to remain a distant prospect, according to Gomes: "From what we know so far, we don't think you'd have to take it from aged 20 until you die. It seems we could start when we're already old, but not too old that we're already damaged. If started at 40, you would have a much nicer window of healthy aging – but I would guess that we have to do clinical trials."

Comments »

|