31st August 2017 Nanomachines drill into cancer cells and kill them within 60 seconds Motorised molecules have been used to drill holes in the membranes of individual cells, and show promise for either bringing therapeutic agents into the cells or directly inducing the cells to die.

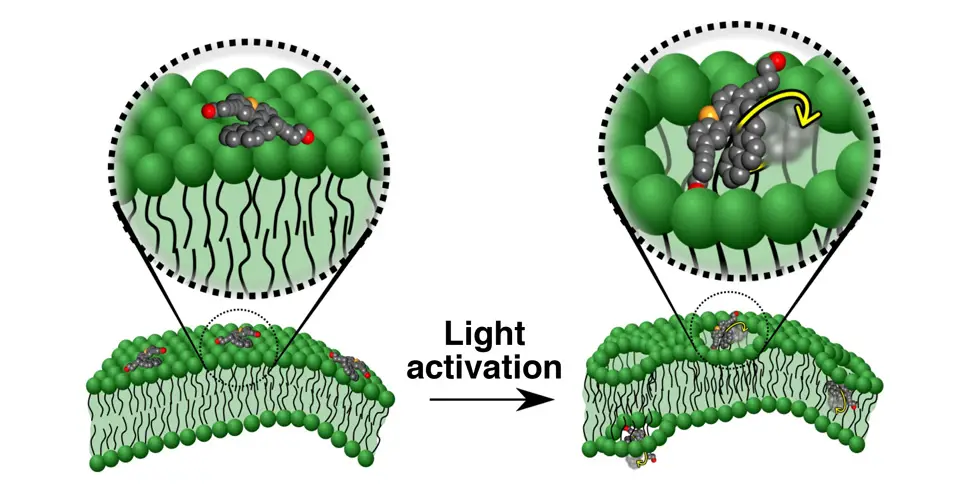

Researchers at Durham (UK), North Carolina State and Rice universities have demonstrated in lab tests how rotors in single-molecule nanomachines can be activated by ultraviolet light to spin at three million rotations per second and pierce membranes in cells. The team developed motors based on the work of Bernard Feringa, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2016. The motor itself is a paddle-like chain of atoms that can be prompted to move in a single direction when supplied with energy. Properly mounted as part of the cell-targeting molecule, the motor can be made to spin when activated by a light source. A team at Rice, led by Professor James Tour, had previously demonstrated molecular motors whose diffusion in a solution was enhanced when activated by ultraviolet light. The rotors needed to spin between 2 and 3 megahertz – 2 to 3 million times per second – to show they could overcome obstacles presented by adjacent molecules and outpace natural Brownian motion (the erratic movement of particles suspended in fluid). "We thought it might be possible to attach these nanomachines to the cell membrane, and then turn them on to see what happened," said Tour. The motors, barely a nanometre (nm) in width, can be designed to target a cell's 8-10 nm lipid bilayer membrane, and then either tunnel through to deliver drugs or other payloads, or disrupt it, thereby killing the cell. They can also be functionalised for solubility or fluorescent tracking. "These nanomachines are so small, we could park 50,000 of them across the diameter of a human hair, yet they have the targeting and actuating components combined in that diminutive package to make molecular machines a reality for treating disease," said Tour. Tour's laboratory created 10 variants – including motor-bearing molecules in several sizes, and peptide-carrying nanomachines designed to target specific cells for death, as well as control molecules identical to the other nanomachines but without motors. The team found it takes only a minute or so for the motors to tunnel through a membrane. In the future, they hope these nanomachines will help target cancers that resist existing chemotherapy. "It is highly unlikely that a cell could develop a resistance to molecular mechanical action," Tour said. The motors were tested on live cells, including human prostate cancer cells. Experiments showed that without an ultraviolet trigger, the motors could locate specific cells of interest, but stayed on the targeted cells' surface and were unable to drill into the cells. When triggered, however, the motors rapidly drilled through the membranes. "[Our] researchers are already proceeding with experiments in microorganisms and small fish to explore the efficacy in-vivo," Tour said. "The hope is to move this swiftly to rodents, to test the efficacy of nanomachines for a wide range of medicinal therapies." "Once developed, this approach could provide a potential step change in non-invasive cancer treatment and greatly improve survival rates and patient welfare globally," said Dr Robert Pal from Durham University, who collaborated. The team's latest study was published yesterday in the journal Nature.

---

Comments »

|