3rd April 2015 Polar bears are unlikely to survive the 21st century As the Arctic region warms and melts, polar bears forced ashore will be unable to gain sufficient food on land. Two-thirds of polar bears will be lost by 2050 and the species could go extinct by 2100.

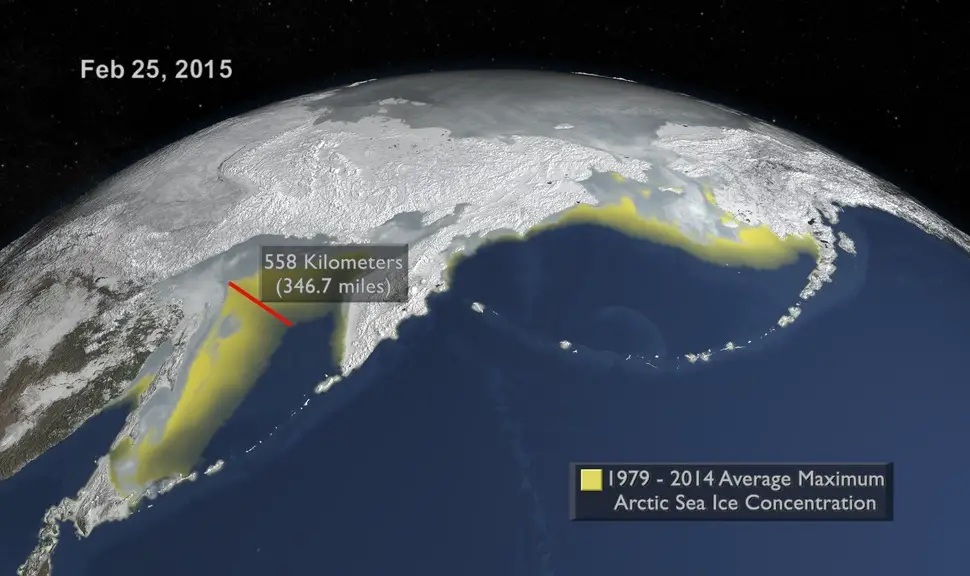

A team of scientists led by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has found that polar bears – increasingly forced ashore due to sea ice loss – may be eating terrestrial foods including berries, birds and eggs. However, any nutritional gains are limited to a few individuals and likely cannot compensate for the lost opportunities to consume their traditional, fat-rich prey – ice seals. “Although some polar bears may eat terrestrial foods, there is no evidence the behaviour is widespread,” said Dr. Karyn Rode, lead author of the study and scientist with the USGS. “In the regions where terrestrial feeding by polar bears has been documented, polar bear body condition and survival rates have declined.” The study authors have published these latest findings in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. They note that over much of the polar bear’s range, terrestrial habitats are already occupied by grizzly bears. Those grizzly bears occur at low densities and are some of the smallest of their species due to low food quality and availability. Further, they are a potential competitor, as polar bears displaced from their sea ice habitats increasingly use the same land habitats as grizzly bears. “The smaller size and low population density of grizzly bears in the Arctic provides a clear indication of the nutritional limitations of onshore habitats for supporting large-bodied polar bears in meaningful numbers,” explains Rode. “Grizzly bears and polar bears are likely to increasingly interact and potentially compete for terrestrial resources.” Last month, the National Snow and Ice Data Centre reported that Arctic sea ice reached its lowest ever extent for the winter, at 1.10 million sq km (425,000 square miles) below the 1981–2010 average of 15.6 million sq km (6 million square miles) and 130,000 sq km (50,200 square miles) below the previous lowest maximum that occurred in 2011. Furthermore, ice thickness during the summer minimum (when the melt season ends in September) plunged by a staggering 85 percent between 1975 and 2012, according to a recent study by the University of Washington. The melting of Arctic sea ice is likely to accelerate as more of the dark water is exposed, absorbing rather than reflecting the Sun's heat. On current trends, the sea is likely to become free of ice during the entire month of September by the 2030s, with up to three months of ice-free conditions by the 2050s.

The study by Rode and her team found that fewer than 30 individual polar bears have been observed consuming bird eggs from any one population, which typically range from 900 to 2,000 individuals. “There has been a fair bit of publicity about polar bears consuming bird eggs,” she said. “However, this behaviour is not yet common – and is unlikely to have population-level impacts on trends in body condition and survival.” Few foods are as energetically dense as marine prey. Studies suggest that polar bears consume the highest lipid diet of any species, which provides all essential nutrients and is ideal for maximising fat deposition and minimising energetic requirements. Potential foods found in the terrestrial environment are dominated by low-fat animals and vegetation. Polar bears are not physiologically suited to digest plants, and it would be difficult for them to ingest the volumes that would be required to support their large body size. “The reports of terrestrial feeding by polar bears provide important insights into the ecology of bears on land,” said Rode. “In this paper, we tried to put those observations into a broader context. Focused research will help us determine whether terrestrial foods could contribute to polar bear nutrition despite the physiological and nutritional limitations and the low availability of most terrestrial food resources. However, the evidence thus far suggests that increased consumption of terrestrial foods by polar bears is unlikely to offset declines in body condition and survival resulting from sea ice loss.” “Why would anyone think this nutritionally poor environment suddenly could support whole populations of the world's largest bears?” says the chief scientist at Polar Bears International, Dr. Steven Amstrup. “There is a big difference between the fact of eating something, and the nutritional value of that eating. While it's tempting to think that polar bears could survive by switching to a terrestrial diet, this paper establishes in no uncertain terms that land-based foods do not offer any hope of polar bear salvation.” “As the sea ice goes, so goes the polar bear,” he concludes. “We generally expect to lose two-thirds of the world's bears by mid-century, and possibly the rest by the end of the century.”

Comments »

|