15th July 2024 First extinction in the United States due to sea level rise The Key Largo tree cactus has been declared locally extinct in Florida, the first extinction event in the United States caused by sea level rise.

We frequently hear about animals and plants threatened by climate change. Increasingly severe and prolonged heatwaves, droughts, flooding, wildfires, hurricanes, melting ice, ocean acidification, invasive species, and the spread of diseases all contribute to disruption of ecological stability and food chains. However, rising sea levels tend to be perceived as a more distant threat, with slower and more incremental changes that are less immediately noticeable and seem unlikely to impact most people significantly until later this century or beyond. In 2016, Australian researchers announced the extinction of Bramble Cay melomys, a rodent located on the Great Barrier Reef's northern tip, which became the first mammal lost due to rising seas. In the United States, meanwhile, no species extinction has been attributed to ocean inundation – until now. This month, scientists are reporting that the Key Largo tree cactus (Pilosocereus millspaughii) is locally extinct in the United States, after the last of these plants disappeared from its only remaining habitat in Florida. Writing in the Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, they believe this to be the first local extinction of a species caused by sea level rise in the country. The plant still grows on a few scattered islands in the Caribbean, including northern Cuba and parts of the Bahamas. The stems can reach more than six metres (20 ft) in height. They have cream-coloured flowers that smell like garlic, attracting bat pollinators, while their bright red and purple fruits catch the eye of birds and mammals. In the United States, however, their population had plummeted in recent years, due to saltwater intrusion from rising seas, combined with soil depletion from hurricanes and high tides.

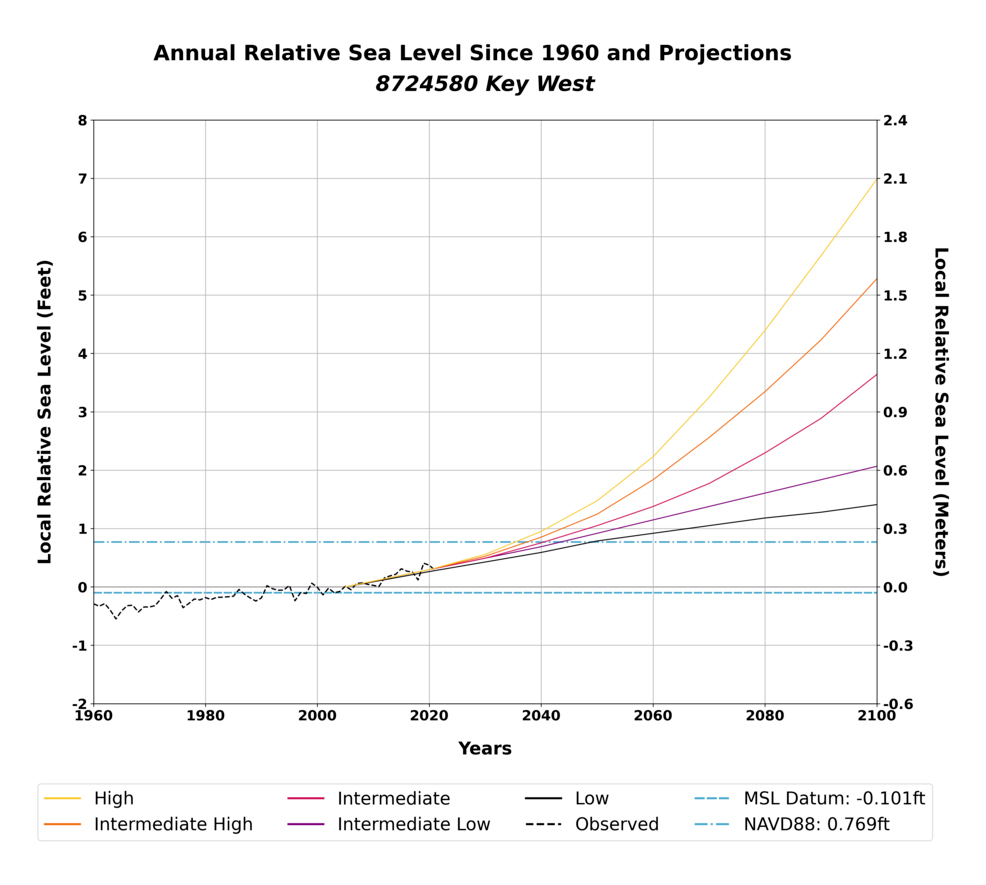

The Key Largo tree cactus grew on a low limestone outcrop surrounded by mangroves near the shore at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park. The site originally had a distinct layer of soil and organic matter that allowed the cactus and other plants to grow, but storm surges from hurricanes and exceptionally high tides eroded away this material until little of it remained. Salt-tolerant plants that had previously been restricted to brackish soils beneath the mangroves slowly began creeping up the outcrop, a clear indication of increasing salt levels. Researchers first discovered the site in 1992, and from 2007 onwards began monitoring the population each year. "In 2011, we started seeing saltwater flooding from king tides in the area," explains James Lange, study co-author and a research botanist at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Florida. So‑called king tides occur a few times a year when the alignment and orbit of the Earth, Sun, and Moon combine to create exceptionally high water levels, and are often exacerbated by sea level rise, leading to more frequent and severe flooding of coastal areas. The decline of the Key Largo tree cactus began to accelerate in 2015 when researchers found only 60 live plants, a 50% drop from two years earlier.

In 2017, category 5 Hurricane Irma swept across South Florida, creating a 1.5 metre (5 ft) storm surge. The highest point on Key Largo is only 4.5 metres (15 ft) above sea level, and large portions of the island remained flooded for days afterward. Once the storm had passed, the Fairchild team conducted triage with several cactus populations throughout the Keys, removing branches that had fallen on cacti and salvaging other material. Conditions were so extreme that biologists had to put out kiddie pools of freshwater to keep local wildlife alive. Two years later, in 2019, king tides left large portions of the island, including the extremely low‑lying outcrop, flooded for over three months. By 2021, only six individual stems remained. With little hope of recovery, the team at Fairchild dug these up, bringing them into captivity. The species is now being cultivated at two nurseries in Florida, while about 1,000 seeds are kept in storage at Fairchild and a vault in Colorado. According to the team, there are "tentative plans" with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to replant some in the wild, further away from the coastline. "We are on the front lines of biodiversity loss," said study co-author George Gann, executive director for the Institute for Regional Conservation. "Our research in South Florida over the past 25 years shows that more than one-in-four native plant species are critically threatened with regional extinction or are already extirpated due to habitat loss, over collecting, invasive species and other drivers of degradation. More than 50 are already gone, including four global extinctions." "Unfortunately, the Key Largo tree cactus may be a bellwether for how other low-lying coastal plants will respond to climate change," said Jennifer Possley, director of regional conservation at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and the study's lead author. "Most people think local extinctions due to climate change and sea level rise are something that will be affecting our grandchildren, but it's happening today."

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|

||||||