11th March 2020 Amazon rainforest could be gone within a lifetime Scientists have published evidence that even large ecosystems can collapse on relatively short timescales. Their paper suggests that once a "point of no return" is reached, the Amazon rainforest could shift to a savannah-type mixture of trees and grass within 50 years.

Some of the world's biggest ecosystems, such as the Amazon rainforest, will collapse and disappear alarmingly quickly, once a crucial tipping point is reached, according to calculations based on real-world data. Writing yesterday in Nature Communications, a team from Bangor University, Southampton University, and the University of London reveal the speed at which ecosystems of different sizes can collapse after a certain threshold – transforming into an alternative ecosystem. Some scientists now believe that many ecosystems are already teetering on the edge of this precipice, with megafires and other destruction both in the Amazon and in Australia. "Unfortunately, what our paper reveals is that humanity needs to prepare for changes far sooner than expected," says joint lead author Dr Simon Willcock of Bangor University's School of Natural Sciences. "These rapid changes to the world's largest and most iconic ecosystems would impact the benefits which they provide us with – including everything from food and materials, to the oxygen and water we need for life." Dr Willcock and his colleagues examined 42 previous examples of this "regime shift" – such as the death of vegetation in the Sahel (a transition zone between the Sahara desert and Sudanian Savanna), desertification of farmlands in Niger, bleaching of coral reefs in Jamaica, and the eutrophication of Lake Erhai in China. Initially, the largest and most complex ecosystems were found to be more resilient to damage than smaller and simpler ones. However, the researchers identified a tipping point, leading to cascade effects and repeated failures throughout a region. As a result, larger ecosystems are more vulnerable to longer-term damage than was previously thought.

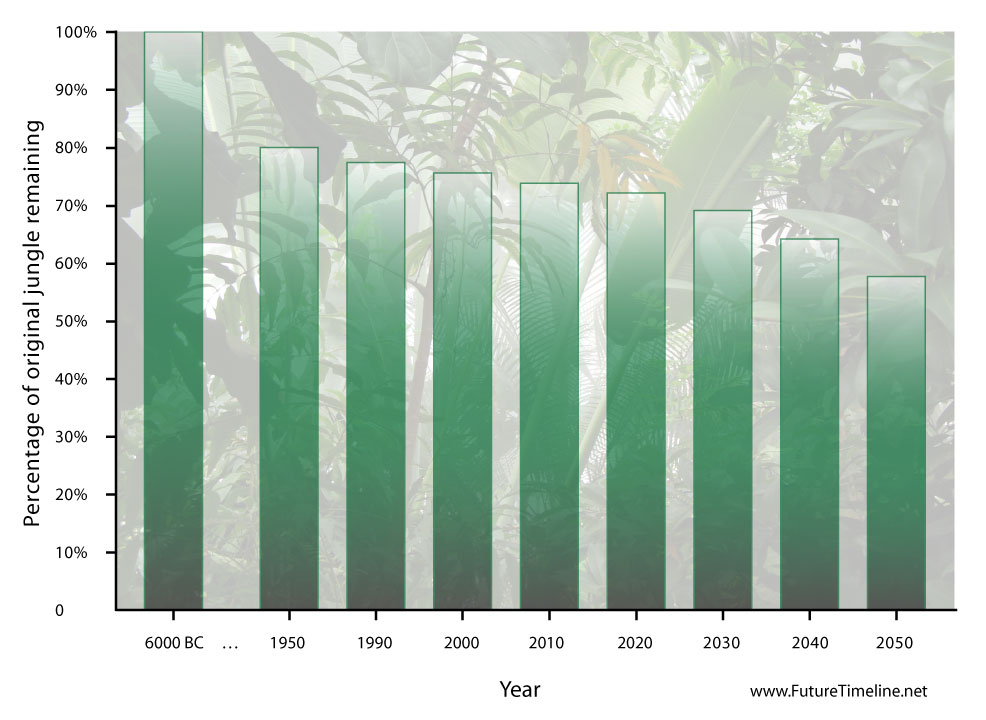

Future Timeline projections of deforestation in the Congo, central Africa. See our prediction for 2040.

"We intuitively knew that big systems would collapse more slowly than small ones – due to the time it takes for impacts to diffuse across large distances," said Professor John Dearing from Geography and Environmental Science at Southampton University. "But what was unexpected was the finding that big systems collapse much faster than you might expect – even the largest on Earth only taking possibly a few decades." Based on their data and projections, the study authors predict an ecosystem the size of the Amazon could collapse within 50 years, while a region the size of the Caribbean coral reefs could collapse within as little as 15 years. "The exponentially increasing global trends of many social and biophysical variables over the past 65 years are widely viewed as unsustainable," the authors write in their paper. "Along with the evidence for increasingly strong reinforcing feedbacks, interactions and couplings between variables, there is growing awareness around the heightened risk of current anthropogenic activities triggering sub-global regime shifts. Combined with the findings presented here, humanity now needs to prepare for changes in ecosystems that are faster than we previously envisaged through our traditional linear view of the world, including across Earth's largest and most iconic ecosystems, and the social–ecological systems that they support." What can be done to slow these collapses? Ecosystems made up of a number of interacting species, rather than those dominated by one single species, may be more stable and take longer to shift to alternative ecosystem states. These provide opportunities to mitigate or manage the worst effects, say the authors. For example, elephants are termed a "keystone" species as they have a disproportionately large impact on the landscape – pushing over trees, but also dispersing seeds over large distances. The authors state that the loss of keystone species, such as this, would lead to a rapid and dramatic change in the landscape within our lifetime. "This is yet another strong argument to avoid degrading our planet's ecosystems; we need to do more to conserve biodiversity," says Dr Gregory Cooper, School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London.

Comments »

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it:

|