3rd August 2015 New technique for nanoscale images of the brain A new technique for obtaining nanoscale images of the brain at higher resolution than ever before is announced by Boston scientists.

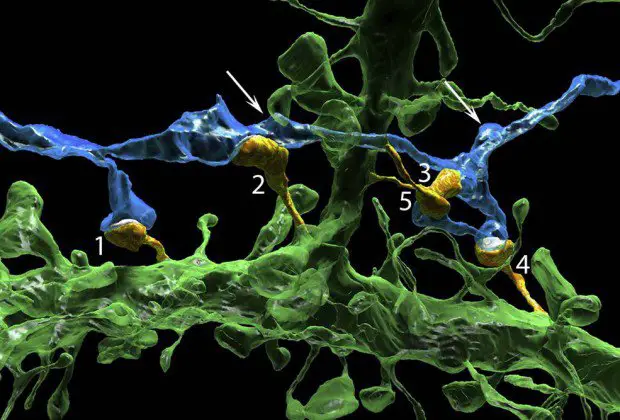

A new imaging tool developed by Boston scientists could do for the brain what the Hubble Space Telescope did for astronomy. In the first demonstration of how the technology works, published in the journal Cell, the researchers look inside the brain of an adult mouse at a scale previously unachievable, generating images at 3 nanometre (nm) pixel resolution. The inventors' long-term goal is to make the resource available to the scientific community in the form of a national brain observatory. "I'm a strong believer in bottom up-science, which is a way of saying that I would prefer to generate a hypothesis from the data and test it," says senior study author Jeff Lichtman, of Harvard University. "For people who are imagers, being able to see all of these details is wonderful and we're getting an opportunity to peer into something that has remained somewhat intractable for so long. It's about time we did this, and it is what people should be doing about things we don't understand." The researchers have begun the process of mining their imaging data by looking first at an area of the brain that receives sensory information from mouse whiskers, which help the animals orient themselves and are even more sensitive than human fingertips. The scientists used a program called VAST, developed by co-author Daniel Berger of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to assign different colours and piece apart each individual "object" (e.g., neuron, glial cell, blood vessel cell, etc.). "The complexity of the brain is much more than what we had ever imagined," says study first author Narayanan "Bobby" Kasthuri, of the Boston University School of Medicine. "We had this clean idea of how there's a really nice order to how neurons connect with each other, but if you actually look at the material it's not like that. The connections are so messy that it's hard to imagine a plan to it, but we checked and there's clearly a pattern that cannot be explained by randomness." The researchers see great potential in the tool's ability to answer questions about what a neurological disorder actually looks like in the brain, as well as what makes the human brain different from other animals and different between individuals. Who we become is very much a product of the connections our neurons make in response to various life experiences. To be able to compare the physical neuron-to-neuron connections in an infant, a mathematical genius, and someone with schizophrenia would be a leap in our understanding of how our brains shape who we are (or vice versa). The cost and data storage demands for this type of research are still high, but the researchers expect expenses to drop over time (as has been the case with genome sequencing). To facilitate data sharing, the scientists are now partnering with Argonne National Laboratory with the hopes of creating a national brain laboratory that neuroscientists around the world can access within the next few years. "It's bittersweet that there are many scientists who think this is a total waste of time as well as a big investment in money and effort that could be better spent answering questions that are more proximal," Lichtman says. "As long as data is showing you things that are unexpected, then you're definitely doing the right thing. And we are certainly far from being out of the surprise element. There's never a time when we look at this data that we don't see something that we've never seen before."

Comments »

|